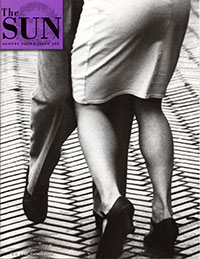

“Men Are From Earth, And So Are Women: Marion Woodman On The Inner Marriage Of The True Masculine And The True Feminine,” Originally published in The Sun magazine, August 2006

Download a PDF of this interview

I’d never danced in church before I took a workshop with Marion Woodman. Being in the chapel of New York City’s Union Theological Seminary was a sort of homecoming for me: five years earlier I had stridden down the middle aisle of that chapel with a newly minted master of divinity degree in my hand. Now a series of seemingly disconnected incidents had brought me back, as if by design, to attend Woodman’s workshop. The psychologist Carl Jung might have chalked it all up to “synchronicity” — a meaningful link between otherwise unrelated events. Woodman, a Jungian analyst herself, would no doubt agree.

I’d attended the seminary to learn about both God and myself, and I had learned much, but something was missing from my education. The Protestant Christian tradition pays little attention to the body. In contrast, Woodman’s work focuses intensely on the body — its pains, its pleasures, and its profound wisdom — as a means of personal growth and spiritual development. And for Woodman, the way to access the treasure buried in the body is through dance, meditation, and dream imagery.

So there I was in Union’s chapel, wending my way through the group of a hundred or so other dancers, only three of whom were men. Later Woodman asked each participant to act out in a dance a particularly meaningful dream image. I picked the sea, and I lay on my back on the slate floor and moved in slow undulations — a bit self-consciously at first — mimicking waves. It brought me back to my childhood on Long Island Sound and was a welcome respite from my demanding job and responsibilities. It also awakened in me the simple joy of being alive. In Bone: Dying into Life (Penguin), about her battle with uterine cancer, Woodman describes an incident in which she says dance saved her life. I was beginning to understand how.

Woodman has spent much of her thirty-year career as an analyst helping people overcome their addictions. She herself once struggled with severe anorexia and believes analysis provides people with the means to free themselves from constraints within and without. The books she has authored or coauthored — there are eleven of them, including Addiction to Perfection, The Pregnant Virgin, The Ravaged Bridegroom (all Inner City Books), and Dancing in the Flames (Shambhala) — are filled with Jungian symbolism, Greek mythology, and lines from Shakespeare, William Blake, T.S. Eliot, and other literary giants. She uses these reference points to explore what it means — and what it takes — to be true to ourselves in a world that wants us to be someone we are not. “Most people in analysis are there because nobody has had time to see them or hear them,” Woodman says. “They’ve spent their lives trying to please somebody else, so they’ve never found their own values.”

The foundation of Jungian analysis is the concept of archetypes, which are images or patterns of behavior that are deeply embedded in the human psyche. Archetypes appear in tribal lore, myths, esoteric teachings, and fairy tales throughout the centuries — and, as products of the unconscious, continue to inform who we are and affect how we behave today. “That people should succumb to these eternal images is entirely normal; in fact it is what these images are for,” Jung writes.

Born in 1928, Woodman spent the first twenty-one years of her career as a high-school English-and-drama teacher in Ontario, Canada, where she was born and raised and still lives. In 1968, while she was traveling in India, a debilitating illness brought her to a crisis and changed her relationship to her body and her Western culture. In the early 1970s, she and her husband, Ross Woodman, moved to London, England, where he studied at London University. It was there that she met E.A. Bennet, a Jungian analyst who transformed her life.

She writes about Bennet in her book Conscious Femininity (Inner City): “He could put me in touch with my feelings when I, who was so smart and rational, couldn’t feel anything. He would just sit there and feel for me until I got the message. Tears would start to run down my face, not because I was sad, but because . . . I was picking up my own feeling from him.” In 1974, guided by her dreams, she enrolled in the C.G. Jung Institute in Zurich, Switzerland. While there she explored her eating disorder, out of which came her first book, The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter (Inner City). Now seventy-eight, Woodman has sold more than half a million books, and a foundation has been created in her honor.

My interest in Woodman’s work goes back fourteen years, to when I read her 1992 book Leaving My Father’s House: A Journey to Conscious Femininity (Shambhala). Although the focus was on women, what she wrote in that book and others spoke to me — a white, middle-class, straight male — as the words of few psychological professionals have. One reviewer has called her “a bridge builder between the male and female worlds.” To understand the human being, Woodman believes, one has to know both sides of the story: the masculine and the feminine. “For Jung,” Woodman says, “the whole process of the soul’s journey is toward the inner marriage of the mature masculine and the mature feminine.”

In the several times I’ve heard her talk, I’ve found Woodman to be an intense speaker, her voice a captivating blend of toughness and grace. For this interview, we talked on four separate occasions, twice in person and twice on the phone. Our first meeting took place the day after the workshop I attended, on a balmy autumn Sunday morning on New York City’s Upper East Side. We’d been trying to find a time and place to meet for more than a year. When I arrived at the apartment where she was staying for the weekend, it took her a while to open the door, because she was unfamiliar with all the locks New Yorkers have. Finally we stood face to face, beaming at each other.

Kullander: Freud called his version of psychoanalysis the “talking cure”: the client talks while the therapist or analyst listens. That has been the prevailing model over the past hundred years or so. But you have always paid attention to the body, both in your practice and in your own psychological development. How did this happen?

Woodman: As a child I was intellectual and lived very much in my head, always aware that my body lagged behind. My father had taught me at home from the age of three, and by the time I went to school I was ahead of the other children my age, so I was pushed up to third grade. I was six years old, and the other kids in my class were eight or nine, so physically I developed a real inferiority complex. I paid little attention to my body and its demands until I got severe sunstroke when I was fifteen. It came on so rapidly that I nearly died. I had no idea what was happening. After that I became more aware of what was going on with my body.

All my life God has spoken to me through illness. My pattern is to go along and have a marvelous time until all of a sudden I’m pulled down by some malady. That’s where the real psychological gravity is for me. Throughout my career I’ve seen people have similar experiences: not paying attention to their bodies and getting sick and sometimes even dying prematurely, or, at the very least, not living their lives as fully as they want. I’ve found that talk therapy is not the best way to help these people. In many instances, it is of little help at all. I decided early on that the body must somehow be involved in one’s psychological healing, because the body can hold on to memories and images that are otherwise inaccessible. You can’t get to them simply by talking about them.

Now I bring groups of women together to work with dream images and the body, and we help each other. For example, say a woman dreams that her mouth is encased in a silver cage. Where does that come from? we’ll ask. Maybe she had parents who scolded her for saying things that “good girls” aren’t supposed to say. Or maybe she had to please someone all her life at the expense of her own growth and development. Or maybe she had a traumatic experience. But we don’t just talk about these possibilities; we guide this woman through a series of body-work exercises that help her dismantle that silver cage. We might begin with movements that open her mouth — literally — and then go on to exercises that focus on the whole body, from the toes to the top of the head, opening the body up and allowing it the full range of natural movement, so that it’s not restricted by fear or overwork or anything else. Then we act out dream images through movement. After a while the cage turns into thin silver wires, and then the silver wires disappear, too.